On a clear night away from the haze of city lights, you may have had the fortune of seeing a dash of light zip across the sky, gone as quickly as it arrived.

For centuries, people have referred to this as a "shooting star," yet the phenomenon, also sometimes called a "falling star," is not a star at all.

What you're seeing is a meteor that could be as tiny as a pebble or grit of sand that has flown through space and smacked into Earth's atmosphere. The ephemeral streak is a rock moving so fast — an average of 45,000 mph, according to NASA — that it blazes as it bombards the air surrounding the planet. Usually, meteors burn up before they ever touch the ground.

But let's put a pin in that for a moment. To fully grasp what a meteor is, it's helpful to know what it isn't. There are many kinds of space rocks, and the terms can be downright confusing.

In short: "Asteroids are rocky, comets are icy, and meteors are much smaller and are the shooting stars that you see up in the sky," said Ryan Park, a near-Earth asteroid expert, in a NASA video.

Tweet may have been deleted

Difference between asteroids, meteors, and comets

Think of an asteroid as a big rocky object — but smaller than a planet — orbiting the sun. Most are found in the asteroid belt, a ring of debris between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. This rocky rubble is left over from the making of the solar system about 4.6 billion years ago. They come in different shapes, and some even travel with their own circling moonlets.

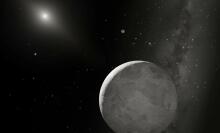

Like an asteroid, a comet also orbits the sun, but it's a bright ball of ice, dust, and rock that formed in the outer solar system. When the ancient dirty snowball approaches the sun, its ice starts to disintegrate. Sometimes shooting stars are confused for comets because they create a glowing streak, but the millions-of-miles-long tail of a comet is its ice and dust vaporizing in space.

Meteors, on the other hand, (or "meteoroids" as astronomers sometimes call them while the rocks are in space), are small chunks of asteroids, comets, or planets that usually broke off during some sort of astronomical collision. Scientists estimate about 48.5 tons of billions-of-years-old meteor material rain down on Earth daily. Most of those space rocks evaporate in the atmosphere or fall into the ocean, which covers over 70 percent of the planet.

Those that survive the brutal inferno of falling through the atmosphere — reaching around 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit due to air friction, according to the American Museum of Natural History — are referred to as meteorites.

Want more science and tech news delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for Mashable's Light Speed newsletter today.

"Asteroids are rocky, comets are icy, and meteors are much smaller and are the shooting stars that you see up in the sky."

More than 60,000 meteorites have been discovered on Earth. The vast majority come from asteroids, but a small sliver, about 0.2 percent, come from Mars or the moon, according to NASA. At least 175 have been identified as originating from the Red Planet. (And, in case you were wondering, Mars gets its fair share of meteorites, too.)

Many space rocks that made the full journey to the Earth's surface are found in Antarctica because they're relatively easier to spot on the vast frozen plains. The dark lumps stand out against the snowy-white landscape, and even when meteorites sink into the ice, the glaciers churning beneath help to resurface the rocks on blue ice fields.

Despite the quantity of meteors pummeling the planet daily, these extraterrestrial sightings are rare, said Don Yeomans, a former planetary scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, before retiring. Only half of the world is in darkness at any given time, and two-thirds of that is over water where hardly anyone lives. Eliminate the areas experiencing bad weather conditions or urban light pollution, too.

"Few people are even looking up at the appropriate moment," he said in a 2010 NASA feature. "When you put it all together, it's almost notable that anybody notices these meteors at all."

The first eyewitnessed meteorite impact

The first-known meteor impact eyewitnessed and recorded was in 1492. In some history books and manuscripts, it was the only major world event mentioned for the year. That's right: The so-called Ensisheim meteorite, named for the town where it was discovered in medieval times, upstaged Christopher Columbus' exploration.

It would take about 300 more years after several other meteorite sightings in Europe and the United States in the early 1800s before scientists accepted that rocks were falling from space. Prior to that, they were generally considered messages from angels or God.

On Nov. 7, 1492, a young boy saw the meteorite as it smashed into a wheat field and brought villagers to the 280-pound black stone. People 100 miles away in the Alps heard the boom of the fireball (yes, another term, used to describe an extremely bright meteorite). Twenty days later, Roman Emperor Maximilian I interpreted the event as a sign from God to declare war on France.

Tweet may have been deleted

Over the years, many museums obtained pieces, and a large amount went to the Vatican. Some small samples have also ended up in private collections through auctions, including one as recently as this spring. The piece, no bigger than a credit card, sold in a Christie's auction for $8,820. The bulk of the meteorite remains in Ensisheim.

"It's the sort of meteorite that if it was just found on its own, and didn't have that 500-year history behind it, it wouldn't be hugely sought after," James Hyslop of Christie's told Mashable.

To increase your odds of seeing a meteor, plan a night of stargazing during a meteor shower. These celestial events happen every year or at regular intervals as Earth passes through the dusty wake of previous comets. Each time a comet zips through the inner solar system, the sun boils off some of its surface, leaving behind a trail of debris. When the planet intersects with the old comet detritus, the result is a spectacular show, with sometimes up to hundreds visible per hour.

Major annual meteor showers

Below are the major meteor showers that repeat every year. How many meteors stargazers will see each time depends on weather and the phase of the moon.

December — January: Quadrantids

April: Lyrids

August: Perseids

October: Orionids

November: Leonids

December: Geminids

Topics NASA