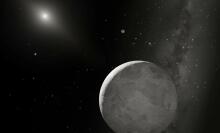

Meteorite hunters scouring Antarctica on snowmobiles discovered something ancient along a stretch of the cold and rocky Allan Hills in 1984 that would later surprise the world. A team of scientists announced 12 years later that the 4-pound Martian meteorite that landed there around 13,000 years ago could be Earth's first glimpse at evidence of life on the Red Planet.

The announcement made headlines. Then-President Bill Clinton even addressed the nation about it on television, recalled Linda Billings, a consultant to NASA’s Astrobiology Program and Planetary Defense Coordination Office.

“It was huge news,” she said. “But over the next few months, the scientific community looked at the evidence presented and the consensus was this is not evidence of microbial life."

On its surface, the meteorite is covered with green, gray, brown, yellow, and blue hues and, if you look closely, you can see burnt orange and gold disks with black and white rims. The scientists behind the life-on-Mars theory proposed that microbe-like indentations and magnetite crystals in the black rims could've been left behind by a tiny Martian organism billions of years ago. In the '90s, many scientists said that wasn't enough to prove anything, despite a small fraction of Earth-bound bacteria producing magnetite crystals.

Sure enough, years later, scientists found that they could recreate the magnetite crystals in the lab by heating carbonates without the help of living organisms. Further research showed that shockwaves could've provided ample heat for this to happen on Mars. The scientific consensus remains today that the strange meteorite doesn't exhibit definitive signs of Martian life.

The emotional roller coaster of awe and disappointment is one we can expect to repeatedly ride in the search for extraterrestrial life. It's a long journey, and the more we find and learn, the harder it becomes to prove that something is evidence of alien life. ALH 84001 raised the bar for scientists; even if a new discovery seemingly checks all the right boxes, there will always be scores of researchers teasing out explanations that disprove a connection to living organisms.

“That's how science works,” Billings said. Until we rule out every possibility, there will always be a question mark.

“Unless there's a rabbit jumping in front of a rover — and we have to make sure it's not a robot — it's going to be difficult,” said Nathalie Cabrol, director of the Carl Sagan Center at the SETI Institute, a not-for-profit research organization dedicated to the search and study of extraterrestrial life.

What is extraterrestrial life?

There isn’t a consensus on what life is, exactly. On the scale of a rabbit, it’s easy to determine, but when we zoom into the microscale, it's much more difficult. Is it something that has a metabolic process like life on Earth? Is it something that takes inputs like gas and energy, uses some of it, and expels the rest of it as a transformed output?

“To me, that's the piping of life,” Cabrol said. “That's what life does. But the question we haven't answered is what life is.”

Cabrol shared an idea.

Looking at the elements that make up the universe, Cabrol said everything is composed of energy (heat) and information (atoms). Taking a cue from how scientists in fields like neuroscience and artificial intelligence are approaching the topic, life at its simplest definition may just be the exchange of energy and information. Well then, isn’t everything in the universe sharing energy and information?

“If you are simplifying the equation, these new models come to a conclusion that the universe is alive, that everything is alive, and that what we recognize as life is only our own ability to understand when information and energy are being exchanged,” she said.

It’s a heady thought, that all the chemical reactions we see taking place in the universe are expressions of life. The collisions of rocks and metals, the heating and cooling of solids, liquids, and gases as they mix with each other and form different compounds, the radiation of stars and gaseous planets, all of it, is life. So perhaps a more apt description for the search for extraterrestrial life would be the search for the manifestation of life’s diversity, Cabrol said, something that we would recognize as life based on our narrow perspective.

With that in mind, what kind of evidence are we looking for that would prove the existence of what we popularly think of as life outside Earth? While we seek out pieces of proteins and DNA, they are very basic molecular structures that have only been observed as components of life on Earth, said Marc Neveu, assistant research scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center at University of Maryland College Park.

“The issue is that they seem to be pretty specific to life on Earth and you could imagine life having emerged elsewhere and using a different set of chemical compounds,” he said.

Signs of life elsewhere that may not look exactly the same as those on Earth are known as "agnostic biosignatures." Scientists studying the origins and future of life in the universe, known as astrobiologists, are constantly looking for what those signs could be, Neveu said. They could be associated with how things are formed, also known as morphology, so certain shapes, indentations, or fossil markings.

“That includes, for example, blobby forms that look like cells.” Neveu said. “If we could see them at different sizes and some that look like they're splitting, that would be good evidence that you have a diversity of growth and reproduction going on.”

It could also be the presence of structures that have similar properties to DNA. DNA has a signature collection of negatively charged phosphorus and oxygen ions that make up its spine so when it replicates, the spines repel each other and allow it to unzip into two strands.

“Those characteristics are thought to be probably universal if you want to have molecules capable of storing and transferring information,” Neveu said. They can be observed with instruments such as spectrometers that measure wavelengths of light that atoms reflect.

Bear in mind that these kinds of signs are fragile, and the likelihood of finding something that’s still perfectly intact is super small. Even with its impressive payload of instruments, the Mars Perseverance rover alone may not be able to determine if something is truly a sign of life, and if it was extremely lucky and found three or four signs on Mars, there's more work to be done. Finding what may be signs of life is just one chapter in the novel of extraterrestrial life. To read the following chapters could take years of study, including future Mars missions, as much as we may want to jump to the epilogue.

As long as the rover doesn’t spot a rabbit hopping on the surface, of course.

The clues to extraterrestrial life

Early on in the exploration of Mars, the planet most similar to Earth in composition, we sought evidence of water, a key ingredient to life as we know it and an indicator of whether that planet may have been hospitable.

Missions like the Mariner 9 and Odyssey spacecraft sent to orbit the Red Planet in 1971 and 2001, respectively, found canyons, riverbeds, and lakebeds on and under the surface, definitive evidence of past waterflow. Further missions have confirmed theories that water in the form of ice is currently present on Mars.

Beyond Mars, entire oceans and rivers of liquid water have been discovered on Saturn’s moons Titan and Enceladus, and Jupiter’s moon Europa.

Water, it turns out, isn’t as rare of a commodity as we previously thought, and water alone doesn’t prove the existence of life, explained Neveu. It’s just a sign that a moon or planet could be hospitable; it's a single chapter in the long, ongoing mystery novel that is the search for life.

“Everywhere we go on Earth that we see water, sources of energy, and sources of nutrients (bio-essential elements), we find that these environments are inhabited — for the most part by microbes,” Neveu said. “These are the three ingredients that we look for beyond Earth to identify places that may be suitable for life. We call this habitability... It doesn't mean the world is habitable necessarily, but you can go in for more detail.”

The next chapter in the search for life covers potential signs of biological activity, namely the presence of certain gases in inexplicable concentrations. One example is the abundance of methane observed on Mars beginning in 2003, and later on Titan.

“These are gases you wouldn't necessarily expect at these abundances given the rest of the atmosphere,” Neveu said of Mars.

He explained that methane has no oxygen atoms in it, whereas most of the rest of the Martian atmosphere is composed of gases with oxygen like carbon dioxide and nitrogen gases.

“If you put them together and let them react, they'll make some energy,” he said. “A lot of microbes use those kinds of reactions on Earth to derive energy and be able to do things, even when there isn't sunlight.”

Some scientists theorized in 2010 that the methane on Titan could come from organisms that pump out the gas as part of their breathing, digestive, and reproductive processes (aka metabolisms), just like many plants, animals, and microbes on Earth. But the Cassini spacecraft that observed Titan beginning in 2004 didn’t have the proper scientific instruments like micro-scale cameras and close-range chemical identifiers to confirm the presence of organisms, so another explanation such as an unknown, chemical reaction coming from the planet's geology — the rocks, minerals, and other elements that make up a planet's structure — is just as likely.

Not far from Titan, Enceladus is pumping geysers of ice and organic compounds into its atmosphere from cracks in its frozen crust. The discovery of diverse organic compounds including nitrogen in 2019 pointed out that these specific compounds could form amino acids, key building blocks of life as we know it on Earth. Amino acids can attach to each other to form proteins, which in turn can form living cells. But scientists haven’t seen the amino acids themselves, nor other evidence of life on Enceladus.

In September 2020, a team of scientists looking at Venus's atmosphere from Earth published a study concluding the presence of phosphine (another gas lacking oxygen, like methane) could be the result of unknown chemical reactions stemming from light or geology, or, as we observe it on Earth, it could be the result of life. The media and the public latched onto that third, more exciting hypothesis.

By November, the scientists made an amendment to the study: There was an error made while processing the data used from the ALMA telescope, casting further doubt on the theory that there could be microbes floating around expelling phosphine in the Venusian atmosphere. Some authors on the study are still confident in their phosphine assertions, but the consensus among the scientific community remains skeptical.

In the search for extraterrestrial life, there is an abundance of clues to look for, threads to pull, and anomalies to pore over. Whether observed on Earth, through the eyes of orbiters, or examined on alien surfaces with rovers, fossil-like indentations, water, gases, and chemical compounds don't prove anything alone. It's a matter of putting everything together and ruling out other options through the scientific method and further research.

Where we are in the hunt for extraterrestrial life

With missions from three countries arriving at Mars in February including NASA’s Perseverance rover, missions like Dragonfly and Clipper set to further explore potentially hospitable moons Titan and Europa, and discoveries of exoplanets in other solar systems that could have Earth-like conditions, scientists are are on their way to writing the next chapter in this ongoing story.

“Maybe the rover can get us to chapter three, which is: There are several signs of life, and now we start to get into a more detailed analysis of the context,” Neveu said. “So the time to ask these questions about how we will handle the process of confirming signs of life or disproving them is really now.”

But as these scientists reiterate, getting to that conclusion will take a lot of time.

“You might not be able to prove that something is something, but we have the tools to demonstrate what it is not,” Cabrol explained. “We're getting close.”

When looking at potential signs of extraterrestrial life, after absolutely every other explanation is ruled out, there will always be an if or a but.

“‘Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence,’” Cabrol said, quoting the late Carl Sagan.

So you can't get your hopes up that when the Perseverance rover lands in the Jezero Crater on Mars, it will stumble upon absolute proof of life within a few months. Even if it finds an unexpectedly clear sign of life, we’d have to wait years for the soil samples it gathers to be brought back to Earth, and cross our fingers that the samples return intact and ready for further testing.

“In my experience, from the time you're starting your project to the time you're able to submit a paper and publish it, it's at least a couple years,” Neveu said. “That's why we have to be patient. I realize it's hard. You kind of want to jump to the conclusion of the book and have your yes or no answer.”

Not only do we need time, missions require money, and funding is tough.

“The science community has developed wonderful plans for these landing missions but the farther out you go in the solar system, the more expensive it gets, the more challenging it gets,” said Billings. “I don't know how many years it's going to take.”

Of course with more evidence comes more interest and more potential for mission funding. But, in the broadest strokes, what would finding alien life really mean for us Earthlings?

“We talk about humanity like it's some kind of monolithic group,” Billings said. “We have so many people living on this planet who wake up every morning wondering if they're going to eat. Do they care? What does this mean to them?”

Cabrol shared a similar sentiment, but pointed to other benefits that these missions bring.

“Some people who are fans of science are going to dig it,” she said. “For people who are not that interested in science, they're going to say, ‘OK we spent billions of dollars to find microbes.’ But what they don't understand is the technology, the development of systems, and the science that went into finding that microbe finds its way back into their daily lives in the form of technology, in the form of services that they have no clue about.”

She pointed out that LASIK surgery stems from the technology developed to assist docking between spacecraft. The valve used to assist your heart when waiting for a transplant stems from inventions for space exploration. The same applies to artificial limbs, robotic arms, baby formula, high-tech sports shoes, early computers, and GPS.

As scientists fine-tune their strategies, improve technologies, and put forth new ideas, we get closer to perfecting how we look for life on other planets.

Despite all the hard work and theorizing, the question still remains, and likely for a long while: Is there anybody out there?